We know software can get complex over time, specially when it comes to state management. More often than not, we find ourselves with tricky user interface logic where things on the screen may not represent the actual system’s state, which ends up being either too vague and leading to a difficult diagnosis of what is the current state, what the next will be and so on…

Modeling states can make our path more clear so we can see all the possibilities, bad and happy ones or even catch bugs a lot earlier than usual.

Finite state machines are modeled for determining which state your application could be in. It is composed of a finite number of states, an initial state, and transitions between each of them. A state describes what is the status of the system at that time. You can think of them as behaviors.

Aside from modeling modern systems, finite state machines are a mathematical concept we can recognize being implemented in many things in the world outside. They are modeled on embedded systems, electronic components, network protocols and whole lot more.

Examples are:

- Traffic light: Green → Yellow → Red → Green …

- Turnstile: Locked → Unlocked

- Revolving door: Push → Rotate

State machines are linear which means you can’t have a state going directly to another, e.g. “idle” → “submitted”.

By using finite state machines you know exactly in which states your application can be, when a machine is a given state, and what the next state is.

Jump to heading Why use state machines

When developing UI logic we tend to rely on boolean variables and conditional statements to display something dynamically on the screen based on a piece of state.

const isLoading = true;

// what "isLoading" does actually mean? did the request succeed?

// is content ready to be shown?

if (!isLoading)

// do something

But booleans don’t express enough what is happening in your application.

For example, you might have seen UI flows where you click something on the screen, it makes a request, then a loading spinner shows up, and later a success message is shown while the spinner is still on the page even though those two pieces of information weren’t supposed to coexist.

So if you can’t trust these isLoading , isFailure or isSuccess boolean flags how can you guarantee these things won’t happen?

What you can do instead is think upfront and describe which possible states might be in your application flow.

A simple state machine can be build-out of a switch statement:

// If you've used reducers before this might look familiar to you

const status = {

LOADING: 'LOADING',

INVALID: 'INVALID',

DISABLED: 'DISABLED',

SUBMITTED: 'SUBMITTED'

}

switch (formState) {

case formState === status.LOADING:

// ...

break;

case formState === status.INVALID:

// ...

break;

case formState === status.DISABLED:

// ...

break;

case formState === status.SUBMITTED:

// ...

break;

default:

break;

}

Now you have a more descriptive and readable way to indicate which of the finite number of behaviors something is in. You still need to handle transitions for each possible state, which can be done through plain functions, but to not get things out of hand with too many switch statements let’s take another approach and use an object syntax instead:

const airplaneMachine = {

initial: "flying",

value: "flying",

states: {

flying: {

on: {

LAND: "landing"

}

},

landing: {

on: {

TAKE_OFF: "flying"

}

}

}

};

const transition = (machine, state, input) => {

const nextState = machine

.states[state]

.on?.[input.type]

return {

...machine,

value: nextState

}

}

const { value } = transition(airplaneMachine, 'flying', { type: 'LAND' })

value // 'landing'

Ok, that looks a lot more readable, doesn’t it? This is looking closer to what we’re going to see on XState later on this post. The best part of it is that you can apply this same concept to any technology you want.

Jump to heading XState

From XState docs:

“XState is a library for creating, interpreting, and executing finite state machines and statecharts, as well as managing invocations of those machines as actors.”

XState state machines are made out of the following building blocks:

- Finite number of states

- Finite number of events

- Transitions

- Initial state and a finite number of final states

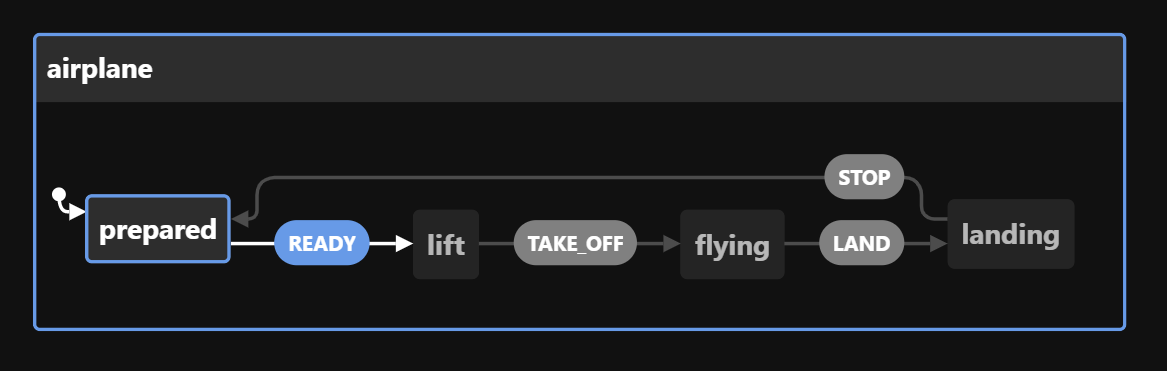

Back to our example, here’s how a FSM is defined using XState:

import { createMachine, interpret } from 'xstate';

const airplaneMachine = createMachine({

id: 'airplane',

initial: 'prepared',

states: {

prepared: {

on: { READY: 'lift' }

},

lift: {

on: { TAKE_OFF: 'flying' }

},

flying: {

on: { LAND: 'landing' }

},

landing: {

on: { STOP: 'prepared' }

}

}

})

const planeInterpreter = interpret(airplaneMachine).onTransition(({ value }) =>

console.log(value)

);

planeInterpreter.start(); // prepared

planeInterpreter.send("READY"); // lift

planeInterpreter.send("TAKE_OFF"); // flying

Here we’re initializing our state machine in the “prepared” state and once we instance an interpreter we can switch between states by dispatching events throughout the app. Each event targets a state, which can be the next one or itself and, you can have more than one event per state.

In order to be better visualize our logic, XState provides an awesome tool where we can test finite-state machines manually:

Jump to heading Handling side-effects and asynchronous data

Besides states and transitions, XState can also handle side effects with actions that actually modify your app’s stateful data.

Although state machine memory is limited to the number of its behaviors, you can work with different kinds of data in your machine by defining them in context, also known as the extended state.

As a side note: This part is a extension of the formal finite state machines concept known as Statecharts that introduces features that complements FSM such as parallel states, nested states and conditional transitions. Statecharts itself it is whole new topic but if you are feeling adventurous you can learn more about them here.

import { createMachine, interpret, assign } from 'xstate';

const airplaneMachine = createMachine({

id: 'airplane',

initial: 'prepared',

context: {

passengers: 0,

},

states: {

prepared: {

on: {

INC_PASSENGER: {

target: 'prepared',

actions: ['incrementPassengers']

}

READY: 'lift'

}

},

// ...

}

}, {

actions: {

incrementPassengers: assign({ passengers: context => context.passengers + 1 })

}

})

interpret(airplaneMachine)

.onTransition(({ context }) => {

console.log(context.count);

})

.start()

.send('INC_PASSENGER')

.send('INC_PASSENGER')

.send('INC_PASSENGER'); // 3

In the example above, we’re defining a piece of data in the machine’s context that is being modified by the action “incrementPassengers” that is triggered once the machine is in the “prepared” state and the increment event is fired. Actions can be declared either on the event “actions” property or in the machine configuration object.

But what if our data doesn’t exist yet?

In order to fetch external data, we can invoke a promise or callback under a state that will resolve as the machine enters that state. Once it is resolved, it will send an event back to the state machine, which can be either onDone or onError.

import { createMachine, interpret, assign } from 'xstate';

function fetchLatestFlight() { /* some api call */ }

const airplaneMachine = createMachine({

id: 'airplane',

initial: 'onboarding',

context: {

flight: null,

},

states: {

onboarding: {

invoke: {

src: fetchLatestFlight,

onDone: {

target: 'prepared',

actions: assign({ flight: (_ctx, event) => event.data })

},

onError: {

target: 'failure',

actions: () => console.error('Failed to retrieve flight data')

}

}

},

prepared: {

on: {

READY: "lift",

CANCEL: 'onboarding'

},

},

failure: {}

// ...

}

})

interpret(airplaneMachine)

.onTransition(({ context }) => {

console.log(context);

})

.start()

/*

flight: {

"passengers":100

"from":"São Paulo"

"to":"Stockholm"

}

*/

Jump to heading Testing State Machines

Testing state machines behaviors is straightforward in general since you don’t need to be tied to the internals of them.

In XState, you can opt to do a pure state transition assertion, for instance when the machine is in a state X and a specific event is triggered, it should be in a certain state Y.

describe('when "TAKE_OFF" event occurs given "lift" state', () => {

it('should reach "flying" state', () => {

const state = airplaneMachine.transition("lift", { type: "TAKE_OFF" });

expect(state.matches("flying")).toBeTruthy();

});

});

But if you’re dealing with async stuff you might as well mock an action or service and assert that when in a given state they’ll update the machine’s context as it is invoked. You can achieve that by using withConfig() like so:

const mockMachine = airplaneMachine.withConfig({

services: {

fetchLatestFlight: () =>

new Promise((resolve) =>

setTimeout(

() => resolve({ passengers: 120, from: "São Paulo", to: "San Francisco" }),

4000

)

)

}

});

describe('when is in "onboarding" initial state', () => {

it("should invoke fetch and reach to prepared state", (done) => {

interpret(mockMachine)

.onTransition((state) => {

if (state.matches("prepared")) {

expect(state.context.flight).toStrictEqual({

passengers: 120,

from: "São Paulo",

to: "San Francisco"

});

}

done();

})

.start();

});

});

Jump to heading Using with React

Finally, we’ve arrived at the framework land. XState provides a handful of hooks to manage an FSM on the @xstate/react package. You can handle the machine state locally using the useMachine hook or globally through a React Context.

Since this is a fairly small example we’re going to keep it implemented in a custom hook:

// useAirplane.js

import { useState } from 'react';

import { useMachine } from '@xstate/react';

import { airplaneMachine } from '../../state/airplaneMachine';

export const useAirplane = () => {

// state

const [plane, setPlane] = useState({

origin: '',

destination: '',

model: '',

});

const [current, send, service] = useMachine(airplaneMachine);

// event triggers

const markAsPrepared = () =>

current.matches('onboarding') ? send('DONE') : send('STOP');

const markAsLift = () => send('READY');

const markAsFlying = () => send('TAKE_OFF');

const markAsLanding = () => send('LAND');

return {

isInPrepared: current.matches('prepared'),

isInFlying: current.matches('flying'),

isInLanding: current.matches('landing'),

isInLift: current.matches('lift'),

plane,

markAsPrepared,

markAsLift,

markAsFlying,

markAsLanding

};

};

useMachine returns the current state object, a send function used to trigger events on given machine and a service that we can use to watch transitions, start, stop and view the state machine configuration.

As we’ve seen in previous examples, in order to see if the machine is in a specific state we can call matches() method with the state name.

In the following lines we’re going to consume the states and events provided by this custom hook on our main component:

import { AirplaneForm } from './components/AirplaneForm';

import { useAirplane } from './components/Airplane/useAirplane';

function App() {

const {

isInPrepared,

isInFlying,

isInLanding,

isInLift,

plane,

markAsPrepared,

markAsLift,

markAsFlying,

markAsLanding,

} = useAirplane();

const onSubmitPlane = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

markAsPrepared();

};

return (

<main>

<AirplaneForm onSubmit={onSubmitPlane} />

<section>

{Object.values(plane).filter(Boolean).length ? (

<>

<span>

{plane.origin} ➡ {plane.destination}

</span>

<div>

<button onClick={markAsLift} className="button">

Lift

</button>

<button onClick={markAsFlying} className="button">

Take off

</button>

<button onClick={markAsLanding} className="button">

Land

</button>

<button onClick={markAsPrepared} className="button">

Stop

</button>

</div>

</>

) : null}

{isInPrepared && <p>✈️ {plane.model} is ready to lift</p>}

{isInLift && <p>↗️ {plane.model} has lifted</p>}

{isInFlying && <p>🛫 {plane.model} flying to destination</p>}

{isInLanding && <p>🛬 {plane.model} is landing</p>}

</section>

</main>

);

}

Essentially, what we’re doing now is adding a few buttons to trigger the transitions between states and a text that will display conditionally based on the state which can only be one at a time.

To see this all in action take a look at the demo below in which you can play around with:

Jump to heading Wrapping up

Alright, that was quite a lot of content to grasp! But as of now, you should be familiar with a different strategy for handling your edge cases and make your overall application logic more declaratively.

Good to mention that this isn’t particular to any framework, so feel free to mix and match this strategy with other technologies or even alongside other state management libraries.

Hope you can leverage this approach on your next projects!